Following the First World War, the art of stained glass placed greater emphasis on expressing the iconographic subject and thus projected itself into the modernity of the 20th century.

Indeed, the suffering caused by the conflict of the First World War fostered among Christian artists a revival of Sacred Art and stained glass, which found a field of application in Reconstruction projects. From then on, to enhance the expression of the iconographic subject, painter-glass artists did not hesitate to fragment their compositions, to favor the use of glass mosaics, to multiply the palette of tones and colors, and even to use new materials such as glass blocks and cement.

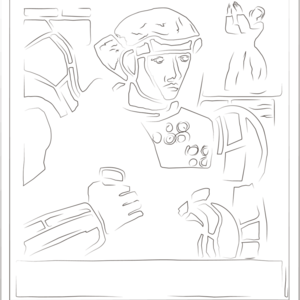

In this context, the Paris workshop of Jean-Hébert Stevens and Pauline Peugniez is among the most committed in this field. While creating stained glass windows for churches that suffered war damage, the couple also participates in the major interwar exhibitions that showcase stained glass panels, such as the exhibition *Art and Modern Religious Furniture*, organized in 1929 at the Galliera Museum, where Peugniez presented the stained glass window *Notre-Dame de la vie intérieure*, and the exhibition *Modern Stained Glass and Tapestries* organized in 1939 at the Petit-Palais Museum in Paris, where Hébert-Stevens presented the stained glass window *Saint George*, created six years earlier.

In 1933, two years after adapting his glass paste technique to the field of stained glass, François Décorchemont also created a round stained glass window depicting Christ teaching the children, which he exhibited that year at the Autumn Salon. Later, he would donate this stained glass window to the Sainte-Foy school in Conches for its catechism classroom.